Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

A study by the University Hospital of Tübingen, has offered intriguing new insights into the origins of type 2 diabetes and obesity.

While poor nutrition and lack of exercise are commonly blamed for obesity, the physiological processes that lead to this chronic condition are more intricate. Recently, researchers from the University Hospital of Tübingen, the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), and Helmholtz Munich have revealed fascinating new perspectives on the development of type 2 diabetes and obesity, highlighting the brain’s crucial role as a regulatory center.

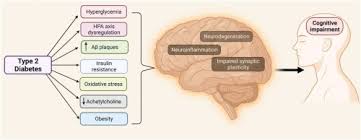

In normal conditions, insulin produces an appetite-reducing effect in the brain. However, particularly in individuals with obesity, insulin fails to properly regulate eating behaviors, leading to insulin resistance. Numerous indicators have suggested that insulin contributes to neurodegenerative and metabolic conditions—especially affecting the brain—with unhealthy fat distribution and persistent weight gain connected to the brain’s insulin sensitivity. The researchers have now demonstrated in the journal Nature Metabolism that even brief exposure to highly processed, unhealthy foods triggers significant changes in the brains of healthy individuals, potentially initiating the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

The research divided 29 normal-weight male participants into two groups. For five consecutive days, one group supplemented their standard diet with 1500 kcal from highly processed, calorie-dense snacks. These additional calories were not consumed by the control group. Following initial assessments, both groups underwent two separate examinations—one immediately after the five-day period and another seven days after the first group had returned to their regular eating patterns.

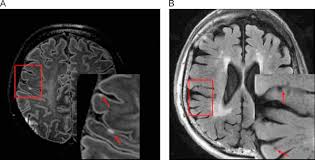

The scientists employed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to examine liver fat accumulation and brain insulin sensitivity. After just five days of increased caloric consumption, the first group not only showed dramatically higher liver fat content, but also exhibited significantly reduced brain insulin sensitivity compared to the control group—a condition that persisted even one week after resuming normal eating habits. Previously, this effect had only been documented in obese individuals.

“What’s remarkable is that our healthy study participants demonstrated a similar decline in brain insulin sensitivity following short-term high-calorie consumption as is typically seen in people with obesity,” explained study leader Prof. Dr. Stephanie Kullmann from the Division of Diabetology, Endocrinology and Nephrology at the University Hospital of Tübingen.

Prof. Dr. Andreas Birkenfeld, who served as the study’s senior author, holds positions as Medical Director of the Division of Diabetology, Endocrinology and Nephrology, Director of the Institute for Diabetes Research and Metabolic Diseases (IDM) at Helmholtz Munich, and sits on the DZD board. In light of these findings, he advocates for additional research into the brain’s role in the development of obesity and other metabolic disorders.